Endurance

11 March 2018

Then the LORD sent poisonous serpents among the people, and they bit the people, so that many Israelites died. 7 The people came to Moses and said, “We have sinned by speaking against the LORD and against you; pray to the LORD to take away the serpents from us.” So Moses prayed for the people. 8 And the LORD said to Moses, “Make a poisonous serpent, and set it on a pole; and everyone who is bitten shall look at it and live.‟ 9 So Moses made a serpent of bronze, and put it upon a pole; and whenever a serpent bit someone, that person would look at the serpent of bronze and live. (Numbers 21.4-9)

And just as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of Man be lifted up, that whoever believes in him may have eternal life. (John 3.14-21)

In the deserts of Egypt, Moses lifted up a bronze serpent, an image on a pole—so that whoever looked on it would live. When we hear this strange story from the Book of Numbers, we’re likely to think that it does not make much sense. Yet, as so often, what seems strange begins to become meaningful if we allow it to fill our heart and mind.

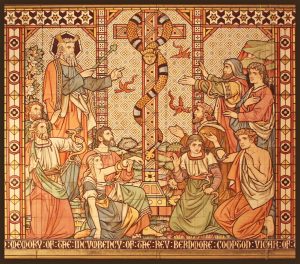

The serpent shimmered against sun and sky, seeming to become a sacred image: a thing of horror, little by little it became a life-giving sign. This is the story about the transformation of a sign. Its meaning is turned around: a sign of death becomes a sign of life. When it is lifted up into the light of God, its meaning is transformed.

So it is also with the cross: the cross, an instrument of torture, is transformed. It becomes and instrument of life. It is taken up into God’s purpose, into God’s meaning. Suffering and death are turned around, becoming ways into God’s future. Just as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, so must the Son of Man be lifted up, that whoever believes in him may have eternal life.

Many Israelites had fallen and died at the serpent’s poisonous bite. Yet when we meditate on the serpent in depth, it begins to reveal a certain wisdom. I says, I believe, that we must go through times of trial, of suffering, of wounding and even death if we would reach the promised land.

That is what it means to be human.

“In the midst of life, we are in death: of whom may we seek for succour but of thee, O Lord, who for our sins art justly displeased?”

You might know those famous lines from the Burial Service in the Book of Common Prayer (1662).

We know from our own experience that, if we would enter into life, we must first experience death. All through our lives, possibilities close off and die, hopes cannot be realised and die, friendships die, and so on. We are subject to a continual breaking, which is sometimes very painful to us. Sometimes we are stung very sharply.

Yet even in our sufferings can bring new possibilities for life and growth; even they can reveal their hidden meaning and power—if we respond to them with dignity and hope. If we lift them up into the light of God, like Moses lifting up an image of a serpent, they too can be transformed. We lift our sufferings up to God, who only can bestow meaning. We wait for them to be deprived of their power over us. We wait for them even to become a source of life at the right time, in God’s time. So, like Israel in the desert, we will find strength the carry on. We put one foot in front of the other, and push on to the promised land.

Where the danger is, there grows the saving power also.

(Holderlin quoted in Heidegger’s Essay concerning Technology (1954 [1977]))

Like a vaccine, evils and dangers can even inoculate us and bring us life—if we respond to them with dignity and hope.

If, however, we curse God and protest against our mortality, we will become utterly poisoned. We will fall into the desert sands, never the rise again. No meaning will be given to us, and the future will close off.

So Moses made a serpent of bronze, and put it upon a pole; and whenever a serpent bit someone, that person would look at the serpent of bronze and live.

When I was thinking of all this, I remembered reading once a book by Viktor Frankl, a psychologist sent to Auschwitz during the War. He survived to write Man’s Search for Meaning (1946). He also believed that everything depends on responding to our sufferings with dignity and hope: if we do that, then even they can bestow meaning, they can become a way into the future for us.

In the book he tells the story of one young woman whose death he witnessed in the camp. He says this

It is a simple story. There is little to tell and it may sound as if I had invented it; but to me it seems like a poem. This young woman knew that she would die in the next few days. But when I talked to her she was cheerful in spite of this knowledge. “I am grateful that fate has hit me so hard,” she told me. “In my former life I was spoiled and did not take spiritual accomplishments seriously.” Pointing through the window of the hut, she said, “This tree here is the only friend I have in my loneliness.” Through that window she could see just one branch of a chestnut tree, and on the branch were two blossoms. “I often talk to this tree,” she said to me. I was startled and didn’t quite know how to take her words. Was she delirious? Did she have occasional hallucinations? Anxiously I asked her if the tree replied. “Yes.” What did it say to her? She answered, “It said to me, ‘I am here — I am here — I am life, eternal life.'” (p.69)

Somehow, no matter how bad things get, God is in the reality of the situation—calling us into life.

Amen.